What if Product Makers Had Bigger Brains?

1. Product Efficiency

A few months ago, I shared a slightly provocative thought: “Product making needs DOGE-like austerity. Department of Product Efficiency. DOPE.” Today, I want to revisit that thought with less flair by offering a more grounded take on AI-driven efficiency, which is a catalyst for my conceptualization of DOPE. I will tie this efficiency to a central theme of “bigger brains” (inspired by Stephen Wolfram) that will enable digital product makers to have a creativity and productivity renaissance unlike we have seen before.

2. Stephen Wolfram

The first internship that took me out of the broke-college-student class was in the summer of 2011 at Wolfram Research—the makers of Wolfram Alpha, Mathematica, etc. I got a chance to meet Stephen Wolfram, the founder and CEO, while working on a project intersecting personal data and social networks. Fourteen years later, Stephen Wolfram is the only CEO I’ve worked for whose work I still follow closely. Perhaps it’s his rare skin-in-the-game “founder-mode” qualities, or my perceptions that he is an underrated innovator, tinkerer, and thinker, whose ideas are way ahead of the masses and cut through the noise of today’s crowded quasi-intellectual landscapes.

I decided to write this piece particularly after coming across Wolfram’s intriguing article and question: “What If We Had Bigger Brains? Imagining Minds beyond Ours”. Its blend of computational theory, neuroscience, AI research, and big-picture metaphysical questions hit a nerve with ideas I’d been chewing on since the 2010s, and even more so after the generative AI boom that started late 2022 / early 2023. This article is about how “bigger brains” (i.e. human cognition supercharged by AI) could break down traditional silos of knowledge and reshape how we think, learn, and create—ultimately reshaping how and what we make, as digital product makers.

3. Bigger Brains

In May 2025, while soaking in the Puerto Vallarta sun, I read Wolfram’s essay. His insights into abstraction, computation, and AI inspired me to revisit my own rough unformulated thoughts on transdisciplinary product making. Although Wolfram wasn’t speaking directly about product teams, I saw parallels…or at least I decided to trace a parallel narrative.

In the essay, Wolfram asks: What if our brains were 1,000x bigger? Instead of 100 billion neurons, what if we had 100 trillion? Imagine minds expansive enough to hold vastly more concepts, detect countless patterns, and navigate abstraction layers currently out of reach.

His core thesis, paraphrased, is that the world is full of “computational irreducibility”: systems that can’t be shortcut, requiring the full logic to unfold. Yet, within that complexity are pockets of reducibility: stable, predictable patterns. Wolfram explains how brains, and intelligences broadly, are pattern-compressing machines. Language, concepts, thinking are all forms of compression. Therefore, bigger brains can do more compressions, deeper abstractions, and richer decision-making.

Wolfram explains how humans, today, operate with roughly 30,000 concepts (i.e. words and mental models) and how bigger minds, biological or artificial, could mean millions of concepts instead of only 30,000. Now imagine if product makers had bigger brains! They’d operate at abstraction levels we’ve yet to imagine, design with building blocks that don’t yet exist, and communicate through languages we haven’t conceived. And most of all, artificial knowledge boundaries, silos such as present in academic and industry disciplines, fragmented workflows that get in the way of cohesive and integrative product making would dissolve.

4. Transdisciplinary Opportunity

Our product organizations, much like our education systems and other institutions, were designed to manage human limitations and scarcities such as time, intelligence, and coordination. Each role trained in isolation, constrained by limited bandwidth, institutional incentives, and guarded responsibilities. This model of knowledge acquisition and propagation emerged in the 19th century, when disciplinary thinking was the breakthrough of its day. Specialization brought depth and order then, but the rigid boundaries it established have been inherited into the present where they now stifle creativity, efficiency, and delight for those making and using products.

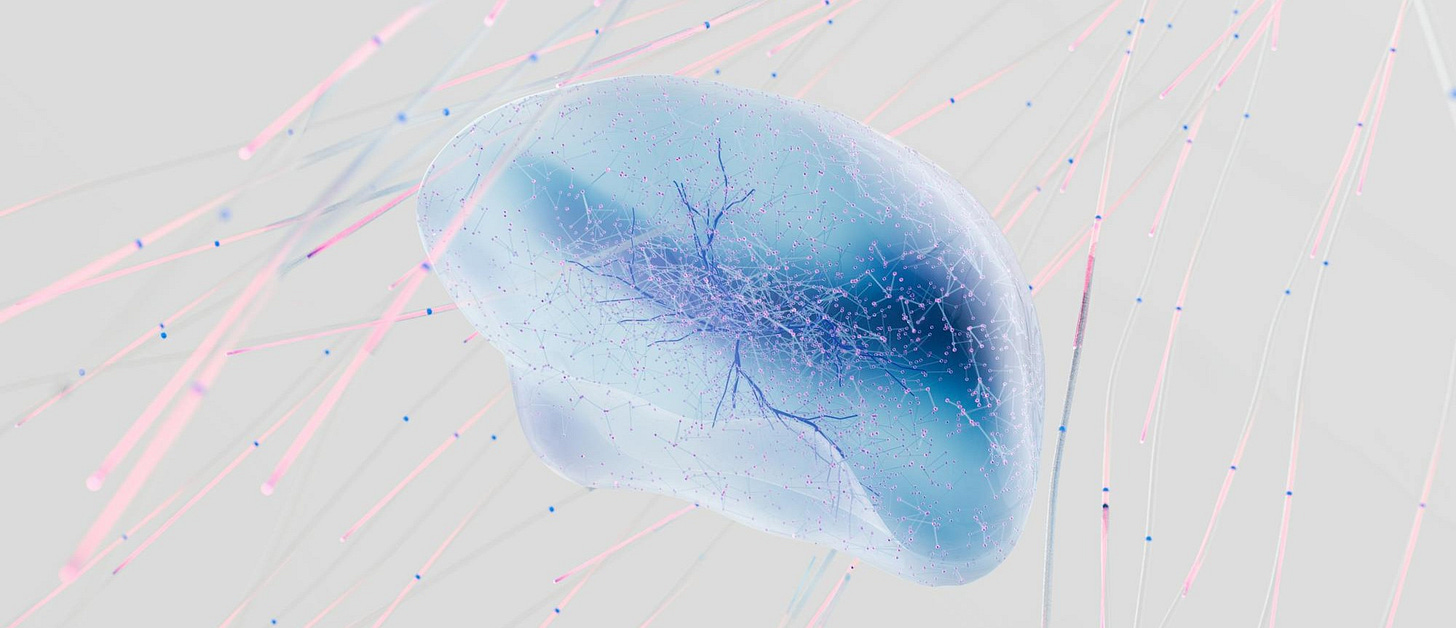

That world is fading fast. AI is rapidly expanding cognitive bandwidth, erasing artificial knowledge boundaries, and democratizing access to information. Interdisciplinary and cross-disciplinary approaches have tried to bridge the gaps, but without the technological force to fully break from the old paradigm, predictable structures persisted and the gatekeepers held their ground. Now, AI is lighting up our collective imagination and enabling product makers to compose across specialties with unprecedented speed and shared understanding.

This, to me, is the Transdisciplinary Product Era that Stephen Wolfram’s vision and question of “bigger brains” points to. This new era is not of the scarcity-mindset that imagines a future through the bleak lens of loss instead of gains (i.e. less roles, less work for humans, etc). Instead, transdisciplinarity is about humanity doing what it does best—expanding and maximizing its capabilities, productivity, efficiency, creativity, and the delight of being human.

And we will get there by making with and from a “bigger brain”—a shared cognitive core with which humans and AI symbiotically co-create like a symphony, but with the spontaneous, innovative flair of jazz improvisation. This collaboration will transcend the limitations of traditional, siloed knowledge systems, enabling groundbreaking concepts, products, and experiences that were previously unattainable in the preceding eras.

Read my previous article that playfully paints a hypothetical yet realistic approach to ways we can begin to create a shared cognitive core in the era of AI.

5. Conclusion

When product makers grow “bigger brains” that are capable of wielding millions of concepts instead of only 30,000, what will they create and how? What will be the most valuable skill? Maybe it will be the ability to work effectively across multiple knowledge domains at once, or moving fluidly between creativity and rationality. Or, perhaps it may be the ability to thrive in micro-sized teams augmented with “agentic” AI entities—analyzing, synthesizing, conceptualizing, realizing, then rapidly refining in ways and at speeds once unimaginable.

Whatever it is, the path to that future is being paved right now by people just like you. These risk-loving, future-driven, ego-minizing individuals (and organization) are not leaning on playbooks, refined roadmaps, or strategy decks but on bold, messy, hands-on experiments fueled by insatiable curiosity and desire to learn, adapt, and thrive. They are doing the kind of learning by doing that Nassim Taleb calls “antifragile”— with a high signal:noise ratio, and extreme upside compared to their downside. More on Taleb in future writing.

Reflection

So, where are you in this AI journey? How are you growing (or shrinking) your brain? Can you start small(er), or take a larger step forward? Should you consume less and create more? One expands your brain, the other shrinks it. How much skin in the game of your life and the life of others do you have, or do you want? Are you willing to finally bet on you or something you deeply believe in? Maybe that’s too big. Maybe try to first run a sprint with an AI collaborator, or try to remove one needless layer of hierarchy and bureaucracy. Replace a team sign-off process with a shared prompt. Draft your thoughts, opinions, and findings. Have someone or an AI give you feedback, then rewrite.

Trust me; it’s painful, messy and not as romanticized as the AI social media “influencers” make it seem. But every major leap is messy and painful, at first. Zoomed in, it’s turbulent, volatile, and extremely fragile. Zoomed out with the passage of time, the curve looks more obvious, smoother and predictable—technology expanding human capabilities and creating prosperity that lasts for generations after. And in this case, it will be no different with AI technology, as it ushers in a creativity and productivity renaissance unlike we have seen before.

6. Afterword

After publishing this piece, I went to the gym, put Wolfram back in my ears, and at the 27:24 mark (video below), he asked: “What might change if we had bigger brains?” Drawing from how neural networks scale, he suggested that with millions of concepts, language might flatten, use fewer nested phrases, enable faster communication and more direct expression, and still support more sophisticated structures.

I couldn’t help but extrapolate this to creativity and productivity, such as in the making digital products. A “bigger brain” would mean fewer disciplinary boundaries and less reliance on layered abstractions needed to collaborate and interact with other humans and technology. Collaboration could be more integrated, inclusive, and cohesive, with fewer handoffs slowing the flow. A more compact and descriptive shared language would become part of that shared connective core. Maybe that language would be code, natural language, a combo, or something else.

Hierarchies would flatten as micro-sized teams move faster without layers of approvals and bureaucracy. Disciplines of the old era, like sales and marketing wouldn’t need to keep existing in separate pipelines. They could also merge seamlessly with design, product, and engineering, turning customer insights or sales goals into instant, co-created changes in the product. UX could expand further into the craft of writing production-ready code, while engineering could more deeply embrace human-centered design and experiential aesthetics. We would move beyond flat, static mental models of “the user” toward live, adaptive understandings that evolve with the product itself. Imagine customer journey maps or service blueprints that are alive, programmable, and connected directly to telemetric product endpoints—in constant feedback loops with real-world usage and micro-sized teams prompting them to adapt and feed back into what’s shipped into production.

Eventually, we’d need new language and structures to describe these ways of working because the old ones would no longer suffice. AI is one of the inevitable catalysts that will and has pushed us to that point. That, to me, is the Transdisciplinary Product Era.